Employer stock purchase plans (ESPPs) are one of those rare benefits that sound complicated but actually come with some very straightforward upsides. At a glance, the deal is often this: you can buy company stock at a discount, usually 15%, and sometimes the plan even offers a look-back provision that lets you buy at the lower of two prices (start or end of offering period). Which means, with almost no effort, you get something like a 15% return just for participating.

For more detailed explanation on ESPP, ESPP Concepts & Tax Explained.

The above all sounds good, right? Still, how to make the most out of it, and more importantly, what not to do, depends on your actual need for the money. And your real view on the stock itself.

If You Need the Money in the Short Term

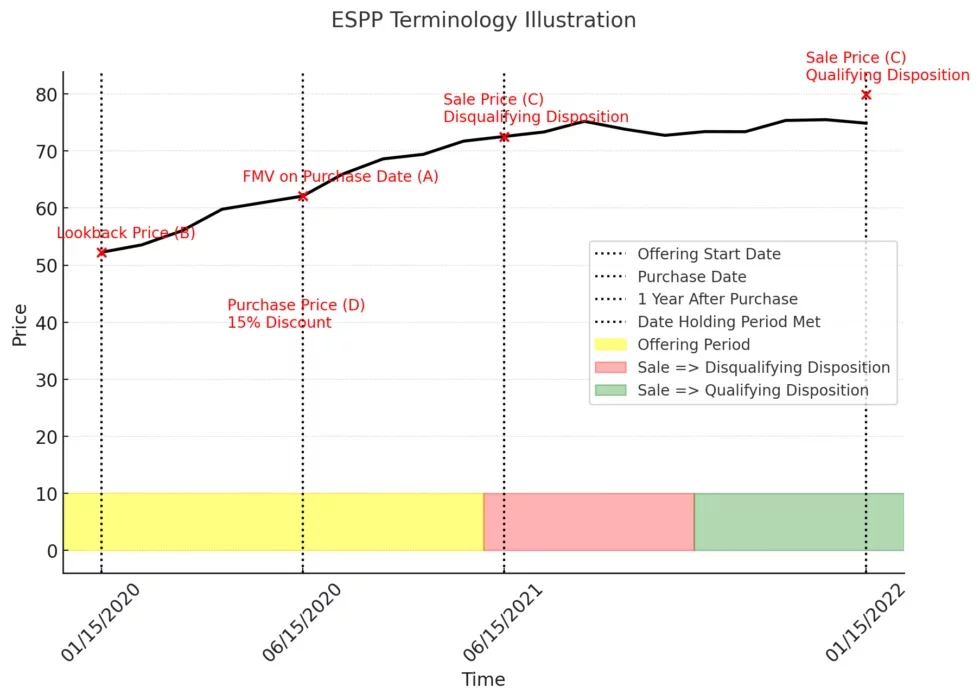

Let’s say this isn’t capital you want to lock up for long term investing. Maybe you’re saving for a house, or just prefer cash flexibility. In that case, it really comes down to timing around taxes. If you sell your ESPP shares right away (or before holding for one year after purchase), the gain will usually be taxed as ordinary income. If you hold it for more than a year (and also two years from the start of the offering), the gain qualifies for long-term capital gains tax, usually a lower rate.

But here’s the catch. Holding it longer just for tax reason only makes sense if you’re comfortable with the underlying stock risk. Stock price could fall during that time. So it’s not free money. It’s a tradeoff. Sometimes better to take the gain early, pay a bit more tax, but sleep better. Especially if you’re using ESPP as more of a cash tool than a long term investing vehicle.

If You’re Thinking About ESPP as a Long-Term Investment

This is where things get more nuanced. Just because you work at a company doesn’t necessarily mean its stock is worth holding. You might like your team, your manager, even the company culture. But that’s not always the same thing as investing in the business long term.

On the flip side, you might dislike your company or feel emotionally disengaged from how things are run lately. That doesn’t always mean it’s a bad investment either. Many excellent companies go through short-term hiccups. Layoffs, leadership changes, bad headlines. Sometimes the underlying business is still very strong, just temporarily unpopular or misunderstood.

Either way, if you’re treating your ESPP as a vehicle for long-term ownership, you can’t just go by gut feeling. And you definitely can’t just assume leadership knows where things are headed. Even the CEO and CFO of your company often don’t have clear visibility on short-term results. That’s not a knock on them. It’s just how dynamic business has become, especially in competitive or fast-moving sectors. So as investors, the most important thing we can focus on is what’s more knowable: the industry and the business model.

Industry First, Then Company

This part is critical and often skipped.

You need to ask: what kind of industry is my company actually in? Not what it says it does in marketing decks, but the real economic engine. Is it an industry with high barriers to entry? Do the players have pricing power? Is there switching cost? Do customers stay for a long time once they’re in? These are signs of a business moat, something that protects profits over time.

Some industries are like this. You’ll find stable, high-margin, slow-changing segments where a handful of winners keep winning. Others are cut-throat, where players constantly undercut each other on price, and any edge quickly disappears. Commoditized sectors. Capital intensive, low margin, highly regulated. It’s hard to win there no matter how “great” a company might seem in isolation.

Find more examples of ‘good’ industries and ‘sectors’ from previous newsletters: quality industries or sectors.

Then once you understand the industry, take a closer look at your own company. Does it dominate a particular segment? Does it have a niche where it’s clearly the leader? Or is it just one of many players chasing growth in a crowded space?

When It’s a Good Business, the ESPP Discount Becomes a Margin of Safety

Now if you do find that you’re convinced, your company has a durable business, strong position, reasonable valuation, then the ESPP discount starts to look like a built-in margin of safety. You’re basically doing dollar cost averaging (DCA) into a stock you already believe in, but at a discount. That 15% discount, or more if the look-back works in your favor, effectively boosts your long-term return. And in investing, that edge compounds over time.

It’s not magic, of course. You still face stock risk like anyone else. But if you believe in the business long term, and the price is already fair, that discount becomes a form of downside protection. You’re entering with a cushion.

But Avoid Overconcentration

This part is important, and people often gloss over it when they’re still optimistic about their company stock. Even if you have high conviction, it’s not wise to let your company stock dominate your entire portfolio. If you already work there, your salary, your career prospects, and your benefits are tied to the same company. Adding a large chunk of your net worth to it just multiplies your exposure to the same risks.

Of course, if you’ve done your homework and believe your company is a long term compounder, then sure, go a bit heavier. Some people have made fortunes this way. But it’s not a strategy for most people. It’s not about pessimism, it’s about diversification. You can hope to strike gold, but don’t forget to carry a shovel in case it’s just another rock.

Summary

Whether you’re using ESPP as a short-term financial tool or a long-term investment vehicle, the key is to be intentional. Understand the tax tradeoffs. Understand the company, the industry, and the risks. And most of all, don’t confuse your employment experience with the investment case. Sometimes they line up. Sometimes they don’t. Either way, the ESPP can still work for you. You just need to know how.